There are many types of grafts, but I have settled on a few that are easiest and most effective for the Proteaceae as stem diameters of the scion and the stock often varies and this dictates the type of graft used. As wound healing starts at the cambium, which is only a few cells thick, it would be impossible to match cambiums all the way stock to scion, so close-proximity and/or intersecting is about all you can aim for. The open faces on the cuts of the scion and stock can brown quickly (just like a bite out of an apple) so the time taken between first cut and completion of the bind should be as short as possible. After the vertical cut on the stock, I close the cut with a clothes-peg while the scion cuts are being done.

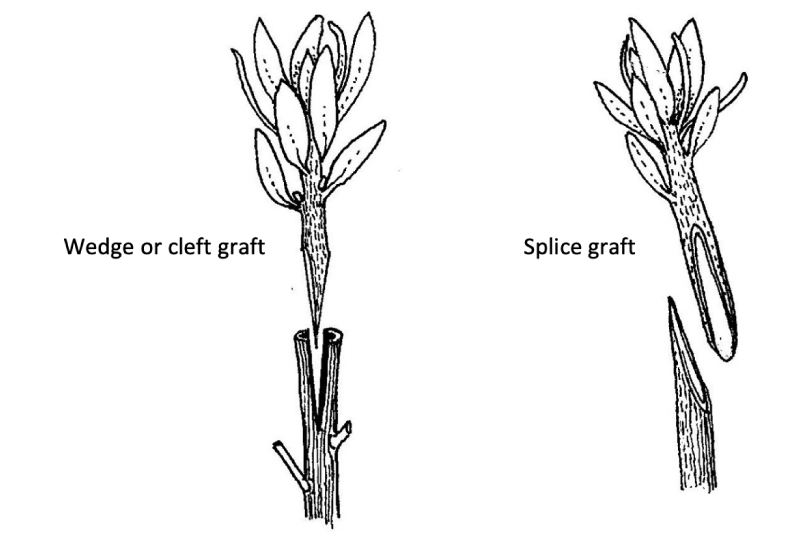

I use the cleft graft (also known as “wedge”) where a vertical cut is made downwards into the prepared stock and a wedge is cut of the scion to match the depth of the stock cut, about four to five times the diameter, the scion is slipped into the cut and tied off. If the cambiums are mismatching, the scion can be set at a slight angle to the stock so that some intersection of cambiums is guaranteed. Alternatively, the scion can be set so that the cambiums are aligning on one side only or the vertical cut can be made off centre on the stock though this would be a last option.

It can happen that a knife slips when the vertical cut is made into the stock and needs a re-cut. There may be no more space on the stock so a re-cut from a ruined vertical cut for a wedge graft needs be changed into a splice graft. For this the single bevel knife is used to make the cuts on both stock and scion. The problem with a splice graft is that the faces of both cuts need to be held together before the bind, so from this perspective is not easy. This splice graft does potentially present more cambium connection.

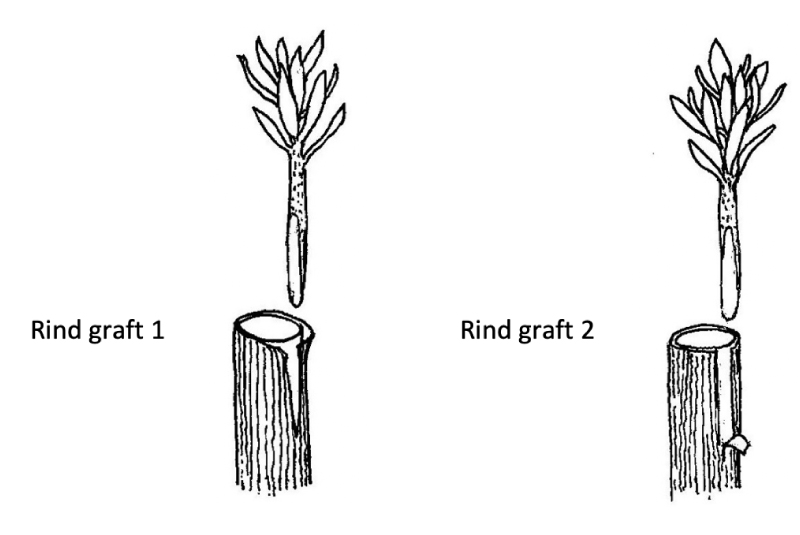

The above techniques are appropriate if the stock and scion diameters are almost the same but with the smaller diameter scions it might be like grafting a matchstick on to a pencil so that the cambium matching is almost impossible. For this a modified rind graft using the U-shaped chisel is a much better option.

A vertical slit is cut in the stock using the short blade knife, no deeper than the cambium layer and a side to side (not a twist) movement of the blade closest to the handle will start the rind to lift. The tip of the blade remains in the bark and is the fulcrum. If needed, with clean thumb nails, the rind can be parted the length of the slit and on both sides of the vertical cut. Alternatively, the bark-lifter can be used. The scion is then scooped with the chisel the same length as the slit in the stock and gently slid behind the parted bark and tied off. The chisel naturally scoops a U-shaped groove in the scion, and this matches the round stock. If the stock is not hardened enough, quite often the bark does not lift easily and I find the bark lifter sometimes damages the cambium when thumb nails cannot do the job. Any damage to the cambium needs to be repaired in addition to callus formation so a variation is to make two vertical cuts the width of the scion (a few millimetres) and the bark between the 2 cuts is peeled downwards to expose the cambium. The scion is scooped with the chisel and inserted into the groove, the flap of the stock is trimmed a bit so that it overlaps the scion tip at the bottom and bound.

I prefer the latter rind graft as with a very thin scion (Protea nana, P. mucronifolia etc) the thinnest part of the scooped scion will nestle inside the vertical sided groove and thus be protected from a too tight binding. The thinnest scooped part of a narrow scion can be only half a millimetre thick, so will very likely be affected by a tight binding in the former rind graft that has only one slit where the bark can press down on the thinnest part of the scion under the binding.

As practise makes perfect and stem hardness varies, a simple jig shown below to hold stems should be part of the learning curve. Think in hundreds of repetitions before starting.